The Conservatives NHS workforce plan is delivering more doctors and nurses

Last year, the government introduced a comprehensive NHS workforce plan. This is the most important positive development in the NHS for decades.

And it is starting to deliver results.

I would never suggest that the NHS could not find a good use for more money. Potential demand for more money for healthcare is, for all practical purposes, infinite.

However, the main problem facing the NHS is not "austerity," as the NHS is almost the only area of government spending to which that approach was never applied. Nor has it been "cuts" over the last forty years under governments of any political party. The most savage cuts in NHS history were made in 1978-9 by the International Monetary Fund under a Labour government, but since the early 1980's total NHS spending has risen faster than inflation under governments of every political persuasion.

The biggest group of problems facing the NHS is a vicious circle around staffing problems - recruitment, retention, high vacancy rates and morale. The morale problem is both an effect and a cause of the others - people have poor morale because they are overstretched and overworked, because they are doing too many people's work, and when they go sick because of the stress or leave or go abroad, it makes the problem worse.

There are a number of reasons for this: I'm not going to pretend that pay isn't one of them, and I support the principle of paying medical professionals and other key NHS staff more.

However, the main underlying reason is that for more than 30 years, under governments of all political colours, this country did not train nearly enough medical professionals.

This problem goes back at least to the early eighties, but reached its apogee in the early years of this century when the Blair government introduced an utterly insane policy of capping the number of places for home students on university medical courses at 4,500 per annum. Amazingly, the BMA actually voted narrowly to support this policy (though to be fair there was a large group of doctors who did not.)

This disastrous approach finally began to change in 2016 when the present chancellor Jeremy Hunt, as health secretary, made the first of a number of increases in the cap, raising it to 5,000 and launching five new medical schools. Last year Rishi Sunak as PM, Jeremy Hunt as Chancellor and Steve Barclay as health secretary launched the NHS Workforce plan.

This plan sets out how thousands more doctors and nurses will be trained in England. It is intended to fill more than 100,000 doctor, nurse and other health worker vacancies and create more to pre-empt future increased demand, save on expensive agency staff and reduce the health service’s increasing reliance on foreign workers.

Unveiling the plan, Rishi Sunak described it as the “most ambitious transformation in the way we staff the NHS in its history”. The prime minister said it would “protect the long-term future of the NHS and this country” by responding to the increased strain that an ageing population is putting on the health service.

The document states that the number of people over the age of 85 is expected to grow by 55% by 2037, and that this risks resulting in a shortfall of between 260,000 and 360,000 staff by 2036-37.

The plan, which will be refreshed every two years, sets out how the NHS will have 300,000 extra doctors, nurses and other health professionals by 2037. It will achieve this in three key ways: training, retention and reform.

How does it work?

The number of places in medical schools each year will rise from 7,500 now to 10,000 by 2028 and 15,000 by 2031, focused on areas where there are too few doctors.

There will be a big expansion in adult nursing training places, taking the total number each year to nearly 28,000 by 2028-29 and nearly 38,000 by 2031-32. This is part of a broader plan to increase the number of nursing and midwifery training places to about 58,000 by 2031-32.

There are plans to expand dentistry training places by 40% so that there are more than 1,100 annual places by 2031-32, and possibly to introduce a tie-in period requiring dentists to commit to working for several years for the NHS after graduation.

There will also be the NHS’s biggest expansion of apprenticeships, including new doctor apprenticeships, with a goal that 20% of all clinical training will be done through these, up from 7% at present. Five-year medical degrees may be shortened by a year.

On retention, the goal is to keep 130,000 more staff in the NHS over the next 15 years through pensions reform, which will make it easier to partially retire or to return to work, and culture change to address staff concerns about overwork and bullying.

How is it be funded?

The NHS will receive £2.4bn in extra funding over the next five years to pay for the planned increase in health professionals, which will also include the training of many more midwives and physiotherapists.

The idea is that the plan will generate some savings, for instance by reducing spending on temporary agency staff by £10bn.

How is it going?

The problem is that it takes years to train a doctor and decades to train a consultant. Delivering this plan will take hard work and vision, and it will take time. But we are beginning to make progress.

Compared with December 2022 there are now almost 6,800 more doctors and over 21,500 more nurses working in the NHS

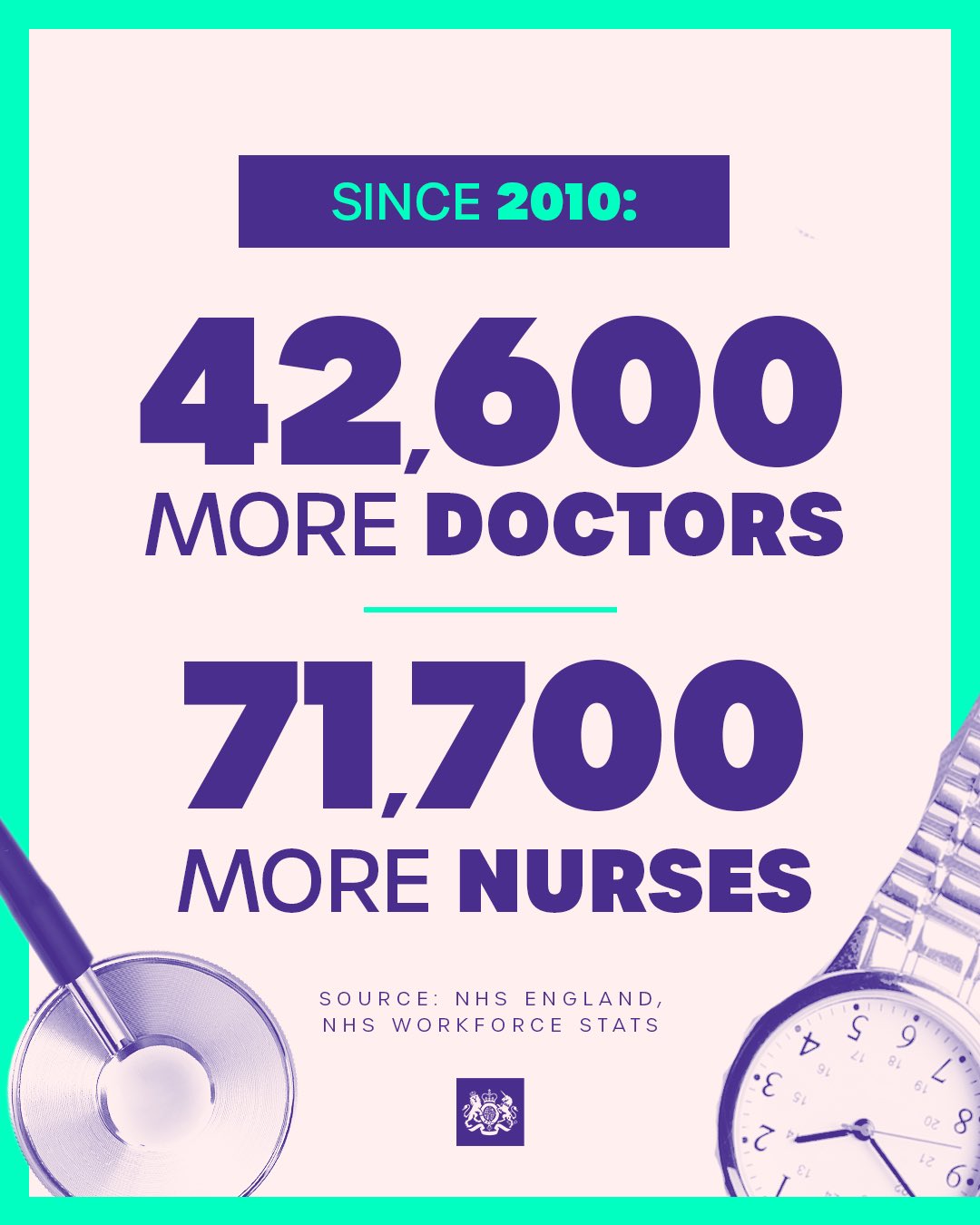

Compared with 2010, there are now over 42,600 more doctors and almost 71,700 more nurses working in the NHS.

We are making progress. If we can stick to the plan and deliver it, Britain will have a better NHS for everyone.

Comments